As with the last essay, I am dictating this post, so my apologies if it gets a little bit rambly in places. On Fairy-Stories is an essay by the great J.R.R. Tolkien that I've wanted to read for quite some time. That time being about a month and a half, which is as long as I've known about it. Either this essay is pretty underground, or I've been living under a rock, but regardless, I was excited to dig into this unearthed piece of Tolkien lore. So when I bought The Stack, it was the first book that I added to the cart. And of course, it was the last to arrive.

Despite my expectations being sky-high thanks to a fellow author on X telling me that this essay changed his life, I really had no idea what it was about. It turns out to cover a wide range of topics related to "fairy-stories" (shocking, I know), such as what they are, their origins, why they're erroneously assumed to be children's tales, their four aspects—fantasy, escape, recovery, and consolation—and finally an epilogue that relates fairy-stories to Tolkien's Christianity.

First, let me say that I'm surprised at how deeply Catholic Tolkien was. (Like I said, I must have been living under a rock. I'm sure this stuff is very well known to anybody who's studied him.) One of the ways my mind works is that I tend to think of people, things, events, concepts, etc. in pairs, and Tolkien was always paired with C.S. Lewis—perhaps unsurprisingly, since they were contemporaries and friends in the Inklings. But until reading the biography about that group, I had always thought of C.S. Lewis as being more predominantly a Christian author. It turns out that's sort of backwards. C.S. Lewis really discovered his Christianity in adulthood, coming to it through rational thought and dialogue with friends, whereas I think Tolkien was brought up in the tradition.

I digress, but it will become relevant later. Back to On Fairy-Stories, starting with—what is a fairy-story?

Fairy-Story

"Fairy-stories are not, in normal English usage, stories about fairies or elves, but stories about Fairy, that is Faërie, the realm or state in which fairies have their being. Faërie contains many things besides elves and fays, and besides dwarfs, witches, trolls, giants, or dragons: it holds the seas, the sun, the moon, the sky; and the earth, and all things that are in it: tree and bird, water and stone, wine and bread, and ourselves, mortal men, when we are enchanted."

One of the things that struck me about this book is just how deeply Tolkien believes in this realm of Faërie, which he calls the Perilous Realm. The way he talks about it, it seems like a real place, almost like one he's visited. Yet even as he expends many words beautifully describing it and its effects, he admits that even he cannot fully capture it.

"Faërie cannot be caught in a net of words; for it is one of its qualities to be indescribable, though not imperceptible."

For that reason, he spends a lot of the beginning of the essay giving negative examples, or things that are marketed as fairy-stories which he doesn't agree are fairy-stories, or giving definitions to other types of tales like "Beast-fables" (think Aesop's fables). But he does pin down some positive characteristics of fairy-stories.

"It is at any rate essential to a genuine fairy-story, as distinct from the employment of this form for lesser or debased purposes, that it should be presented as 'true.'"

I think many of us are quite familiar with fairy-stories these days. The Lord of the Rings is a quintessential fairy-story. But any modern fantasy which presents its world as if it's true counts. My books certainly do, as do most—maybe all—of the indie fantasy books I've read. A counterexample would be anything that is framed as if it's a story within the primary world, maybe just being told by normal people on normal Earth. Or a story that's revealed to be a dream at the end. I think most authors would avoid these sorts of things just because they're bad tropes.

I am curious what Tolkien would have thought of portal fantasy. It's certainly presented as if the world on the other side of that portal is true and that there's like a hidden world underneath or apart from Earth. But one of the examples he gives of what he doesn't consider a fairy-story is Alice in Wonderland, which I haven't read in a while, but I've always held it in my mind as a quintessential portal fantasy. Maybe Tolkien would disagree.

Origins

On the question of the origins of fairy-stories, Tolkien says he will "pass lightly over the question," because he is "too unlearned to deal with it in any other way." He says we're faced with the same problem that archaeologists encounter with the debate between "independent evolution of the similar, inheritance from a common ancestry, and diffusion at various times from one or more centers."

"The history of fairy-stories is probably more complex than the physical history of the human race, and as complex as the history of human language. All three things: independent invention, inheritance, and diffusion, have evidently played their part in producing the intricate web of Story. It is now beyond all skill but that of the elves to unravel it."

I should mention that Tolkien commonly calls the inhabitants of Faërie elves. But this part got me thinking, because saying that the history of fairy-stories is more complex than human history, and as complex as the history of human language, is quite a big claim. One I'm not sure I agree with. If by the physical history of the human race he means the complete and total history of everything that's happened around the world, surely that includes the development of fairy-stories and would therefore be a larger category. But maybe he only equates the history of fairy-stories with the history of human language, because they're more abstract. It's a bit of a separation of mind and body here, and I'm not sure it's warranted.

Nevertheless, he goes on to talk about the human mind's power of abstraction.

"The human mind, endowed with the powers of generalization and abstraction, sees not only green-grass, discriminating it from other things, but sees that it is green as well as being grass. When we can take green from grass, blue from heaven, and red from blood, we have already an enchanter's power."

I interpret what he is calling Faërie to be all of the stories, myths, ancient wisdom, cultural knowledge, and attractors instantiated in the network of human minds and stable over time. It brings up an interesting philosophical point, because Tolkien speaks of it like it's just another realm out there, and human minds are communing with it in some way: not just listening, but also actively creating.

"We may put a deadly green upon a man's face and produce a horror; we may make the rare and terrible blue moon to shine; or we may cause woods to spring with silver leaves and rams to wear fleeces of gold, and put hot fire into the belly of the cold worm. But in such 'fantasy', as it is called, new form is made; Faërie begins; Man becomes a sub-creator."

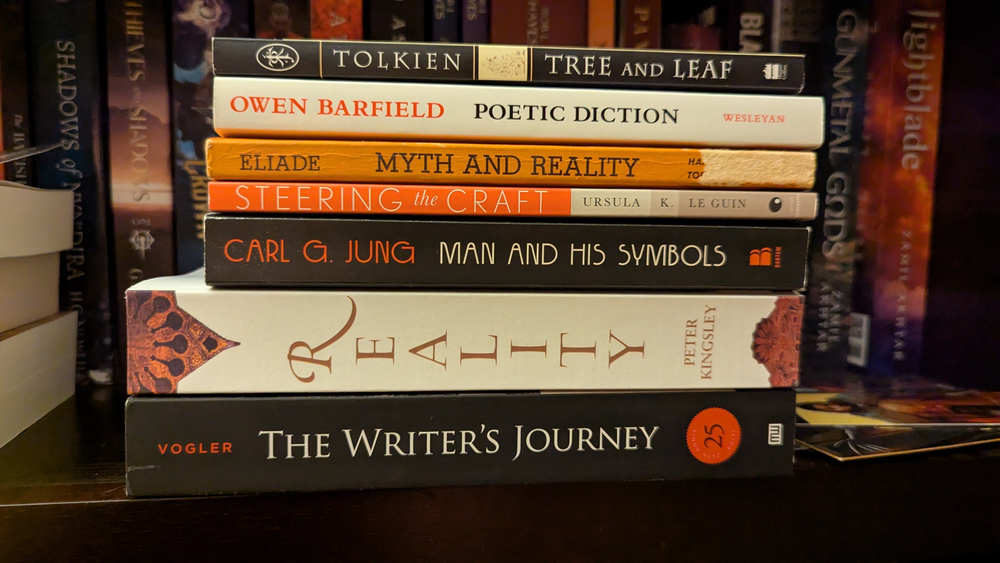

One compelling idea Tolkien puts forth, which pairs very nicely with the Owen Barfield book I just read, is that we essentially can't help it. We create almost instinctively. In merely talking about what's happening, we hypothesize, we tell stories, and these stories, over time, become more poetic as the meaning of their words changes and their wider cultural knowledge is lost. But not all is lost: the narratively or emotionally salient bits remain. That drives a selection effect. People repeat those stories; they gain memetic traction.

But those stories only exist because they correspond to actual things in nature—and to the gods:

"Which came first, nature-allegories about personalized thunder in the mountains, splitting rocks and trees; or stories about an irascible, not very clever, red-beard farmer, of a strength beyond common measure, a person (in all but mere stature) very much like the Northern farmers, the bændr by whom Thorr was chiefly beloved?"

Rather than assuming that nothing actually exists corresponding to Thor:

"It is more reasonable to suppose that the farmer popped up in the very moment when thunder got a voice and face, that there was a distinct growl of thunder in the hills every time a storyteller heard a farmer in a rage."

"If we could go backwards in time, the fairy-story might be found to change in detail, or to give way to other tales, but there would always be a fairy-tale as long as there was any Thor. When the fairy-tale ceased, there would be just thunder, which no human ear had yet heard."

This is Tolkien telling us that sub-creation is instinctual, a core part of human nature. We cannot help but create fantasy, and it is one of the oldest forms of human behavior we know of.

Fantasy

"The human mind is capable of forming mental images of things not actually present. That the images are of things not in the primary world is a virtue not a vice. Fantasy is, I think, not a lower but a higher form of Art, indeed the most nearly pure form, and so (when achieved) the most potent."

Here's another bold claim, that fantasy is the most nearly pure form of Art. A bit snobbish, Professor? Actually, Art is a term Tolkien defines as "the human process that produces by the way (it is not its only or ultimate object) Secondary Belief"—i.e. belief in Faërie. If his logic isn't clear yet, don't worry. We'll come back to it shortly. First, a short detour about the weakness of fantasy: its difficulty to achieve.

"'The inner consistency of reality' is more difficult to produce, the more unlike are the images and the rearrangements of primary material to the actual arrangements of the Primary World. It is easier to produce this kind of 'reality' with more 'sober' material. Fantasy thus, too often, remains underdeveloped; it is and has been used frivolously, or only half-seriously, or merely for decoration: it remains merely fanciful."

As a fantasy author, I can attest that maintaining the inner logic of your story is extremely difficult, even when not dealing with outlandish images. It takes a lot of skill to achieve. Not to toot my own horn, I've done a reasonably good job with the Sibling Suns, but don't think I've quite achieved what Tolkien says fantasy should aspire to:

"To the elvish craft, Enchantment, Fantasy aspires, and when it is successful of all forms of human art most nearly approaches."

Enchantment he defines as that which "produces a secondary world into which both designer and spectator can enter, to the satisfaction of their senses while they are inside, but in its purity it is artistic in desire and purpose." There's that inner consistency of reality again. And now we can clarify his logic about why Fantasy is the most nearly pure form of Art.

His stipulation is that Art, among other aims, produces Secondary Belief. Enchantment is the pure case of the aim; Fantasy is the human art that aspires to Enchantment, and when it succeeds, comes closest to it. Therefore, successful Fantasy is the most nearly pure human art—only nearly pure because it cannot quite reach the heights of elvish craft.

It's wonderful that in addition to writing this essay to convey his philosophy, we have such an amazing example of it put into action in The Lord of the Rings. It is consistently praised as the story with the best worldbuilding—not Enchantment itself, but about as close as human art can get. That can be attributed largely to his depth of understanding and passion for the Art of Fantasy.

Tolkien is also wise. He knows that all light casts a Shadow.

"Fantasy can, of course, be carried to excess. It can be ill done. It can be put to evil uses. It may even delude the minds out of which it came. But of what human thing in this fallen world is that not true?"

A hint of Tolkien's faith comes through here in the mention of "this fallen world." But it is front and center in his beliefs about the importance of fantasy.

"Fantasy remains a human right: we make in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker."

That sentiment is put beautifully in a passage from a letter that he wrote to C.S. Lewis:

Man, Sub-creator, the refracted Light

through whom is splintered from a single White

to many hues, and endlessly combined

in living shapes that move from mind to mind

Epilogue

That segues into the epilogue of the essay, which goes into depth on Tolkien's religious beliefs. First, let me pull in a passage from a prior section I'm skipping past, where Tolkien talks about the, by now, fairly well-publicized concept of eucatastrophe.

"Tragedy is the true form of Drama, its highest function; but the opposite is true of Fairy-story. Since we do not appear to possess a word that expresses this opposite—I will call it Eucatastrophe. The eucatastrophic tale is the true form of fairy tale, and its highest function.

The consolation of fairy-stories, the joy of the happy ending, or more correctly, of the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous 'turn' (for there is no true end to any fairy tale): this joy, which is one of the things which fairy-stories can produce supremely well, is not essentially 'escapist' nor 'fugitive'. In its fairy tale—or otherworld—setting, it is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief."

As Tolkien coined the term eucatastrophe, everybody knows of it as the moment when Frodo decides to keep the One Ring for himself, but because of Gollum's selfish intervention it ends up in the fires of Mount Doom anyway. But the example Tolkien gives is bolder. He says that insofar as the eucatastrophe denies universal final defeat, it is evangelium—"good news" in Latin. Gospel. It echoes the Christian good news that ultimate defeat is overturned. He says the experience of this Joy within Fantasy may be a "far-off gleam or echo of evangelium."

"The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind, which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories. They contain many marvels—peculiarly artistic, beautiful, and moving: 'mythical' in their perfect, self-contained significance; and among the marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable eucatastrophe. But this story has entered History, and the primary world; the desire and aspiration of sub-creation has been raised to the fulfillment of Creation. The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man's history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. This story begins and ends in joy.

Is this controversial in Christian circles? I can imagine Christian family members taking issue with the fact that he says the Gospels contain a fairy-story. But then, they wouldn't know entirely what he means by "fairy-story." I find the sentiment very beautiful and moving.

"It is not difficult to imagine the peculiar excitement and joy that one would feel, if any specially beautiful fairy-story were found to be 'primarily' true, its narrative to be history, without thereby necessarily losing the mythical or allegorical significance that it had possessed. It is not difficult, for one is not called upon to try and conceive anything of a quality unknown. The joy would have exactly the same quality, if not the same degree, as the joy which the 'turn' in a fairy-story gives. Such joy has the very taste of primary truth. (Otherwise its name would not be joy.) It looks forward (or backward: the direction in this regard is unimportant) to the Great Eucatastrophe.

"The Christian joy, the Gloria, is of the same kind; but it is pre-eminently (infinitely, if our capacity were not finite) high and joyous. Because this story is supreme; and it is true. Art has been verified. God is the Lord, of angels, and of men—and of elves. Legend and History have met and fused."

This goes back to his hypothesis on the origins of fairy-stories. He mentions the selection effect that occurs because elements of story are narratively and emotionally resonant. In the case of the Gospels, there's an emotionally resonant sense of Joy, the preeminent eucatastrophes of the Birth and the Resurrection of Christ, that, along with the historicity, cements the Christian Story as true to Tolkien.

And that is what Fantasy has the power to recapitulate, in some lesser degree, when it is written by a master like J.R.R. Tolkien.