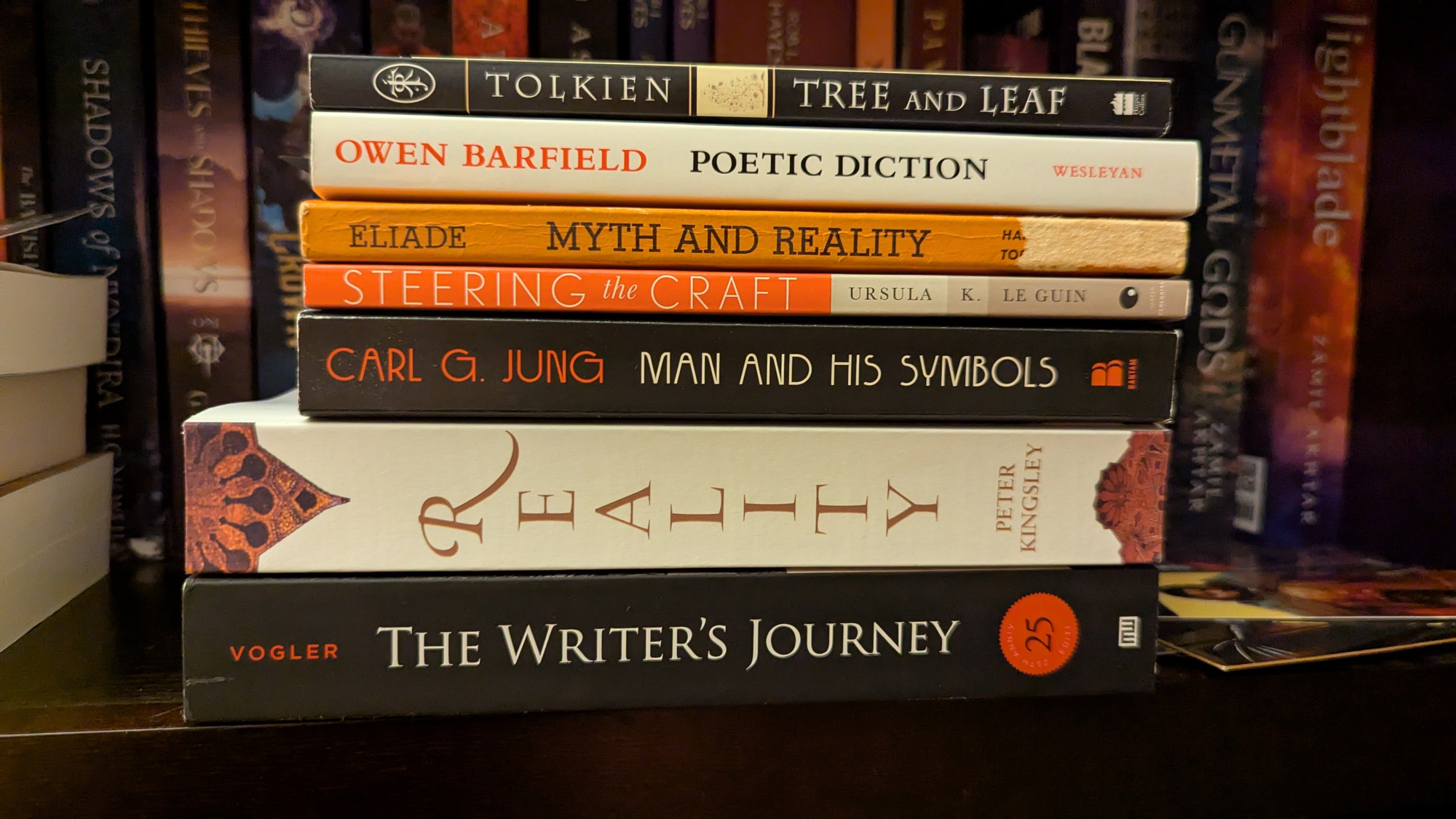

I'm trying something new here. I recently picked up a stack of books that interest me all centered around mythology, language, fantasy, psychology, archetypes, and the nature of what is real. These topics have been resonating with me recently as an author, and in reading these books, I want to do more than just read them and put them down. I want to sit with the ideas for a while after turning the last page.

I figure that means I should write about them.

That's what this is. Except I'm not writing this post, per se. Instead, I'm dictating it and using a transcription software to put it to text, with a bit of editing to clean it up. This post may seem a little bit more rambly, but that's because it's off the top of my head. I just want to get my raw thoughts for this book down.

Rather than write this like a book review, I'm just going to share all of the underlined and highlighted text that resonated with me as I read the book, then share my thoughts on each of the snippets.

For context, this book, Poetic Diction by Owen Barfield, was beloved by Tolkien and Lewis. Barfield was an infrequent member of their Inklings literary group that would meet around Oxford. C.S. Lewis wrote to Barfield about the influence he had on Tolkien's philosophy:

"You might like to know that when Tolkien dined with me the other night he said, apropos of something quite different, that your conception of the ancient semantic unity had modified his whole outlook."

In Poetic Diction, Barfield puts forth the argument that over time language becomes less poetic because, as rational beings, we cannot help but separate all of the different meanings out of rich older words to increase their specificity. The example he gives in the book is the Latin word spiritus. In ancient days, this word meant something akin to (but not exactly) breath, spirit, and wind all at once. Whereas now we have three different words to describe those phenomena.

The book covers many topics surrounding the idea of poetry, like who is responsible for the creation of meaning in language, things of that nature. For example, he discusses the role of the poet and how much of poetry can be ascribed to the poet versus how much exists in the background, what Barfield calls the "joint-stock"—which I interpret as similar to what Jung calls the collective unconscious.

II - The Effects of Poetry

/* (I've skipped chapter one because it only contains some examples of poetry Barfield refers back to throughout the book.) */

This chapter discusses the effects of poetry—that is, how it affects the mind and consciousness and gives rises to an "aesthetic experience."

"The actual moment of the pleasure of appreciation depends upon something rarer and more transitory. It depends on the change itself. If I pass a coil of wire between the poles of a magnet, I generate in it an electric current—but I only do so while the coil is positively moving across the lines of force...

"So it is with the poetic mood, which, like the dreams to which it has so often been compared, is kindled by the passage from one plane of consciousness to another."

I really like this analogy of poetry to the electromotive force. It does a good job capturing the image of electrical current only being stimulated when the magnet passes near the wire. In the same way, this change in state of mind, this aesthetic experience, only occurs at the precise moment that the poetry passes through your consciousness.

"If we are to feel pleasure, we must have change. Everlasting day can no more freshen the earth with dew than everlasting night."

And then he brings it all home with this incredibly beautiful turn of phrase. Barfield is certainly opinionated, and he proposes that this is in fact the purpose of poetry: to feel these changes of consciousness. That is where the true joy in hearing poetry or reading poetry actually lies.

"Taste is formed in those moments when aesthetic emotion is massive and distinct; preferences then grow conscious, judgments then put into words will reverberate through calmer hours; they will constitute prejudices, habits of apperception, secret standards for all other beauties. A period of life in which such intuitions have been frequent may amass tastes and ideals sufficient for the rest of our days."

This certainly rings true for me. I feel even now, though I'm only 34 years old, that I've already experienced many of the stories that will form my taste and the high bar that, I assume, will persist for the rest of my life. And these were certainly the stories which aroused the most acute emotional reaction, whether good or bad.

Strangely enough, I think the darker stories resonate a bit more for me. Events like Ned Stark's beheading, or the Eclipse in the Golden Age of Berserk—those things will stick with me for the rest of my life. I fear there are few of those world-shattering narrative moments remaining in my life. But I hope I'm wrong about that.

"On those warm moments hang all our cold, systematic opinions; and while the latter fill our days and shape our careers it is only the former that are crucial and alive."

Emphasis mine. Such a perfect pair of adjectives. These stories really do live in us, and we retell them, spread them to new minds for them to fall in love with them. They are living things. And crucial—they are the way that we make sense of this world. Stories, more than anything else, instill values of good and evil, of what's important, and how to live and change. So I totally agree with him on this.

I don't agree with everything in the book though. For example, he says:

"For the most elementary distinctions of form and color are only apprehended by us with the help of the concepts which we have come to unite with the pure sense datum. And these concepts we acquire and fix, as we grow up with the help of words—such words as square, red, etc. On the basis of past perceptions, using language as a kind of storehouse, we gradually build up our ideas, and it is only these which enable us to become 'conscious', as human beings, of the world around us. There is, therefore, nothing pretentious or dilettante in describing my experience as 'an expansion of consciousness.'"

He's saying that we can only understand things that we're looking at once we can affix labels to them. And in some sense, I think that's true—but the examples he gives: square, red; I think babies tend to understand those concepts before attaining language. I've got some firsthand experience here. My son is eight months old now, and he certainly understands and is attached to his giraffe toy, even though he certainly doesn't know it's called a giraffe.

Maybe I'm missing the point. But even though I don't fully agree this is how it works, I do like the idea. He calls it an "expansion of consciousness" when you have an aesthetic experience. He goes on to say,

"While this expansion (knowledge) may remain as something of a permanent possession (wisdom), my aesthetic pleasure will still, in the case under review, only accompany the actual moment of expansion, as it before accompanied the moment of change.

This is something that I play with in the Sibling Suns books. An expansion of consciousness literally happens when the characters go through a moment of change called a Deluge. They experience the memories, emotions, and sensory experiences of the monster emitting this psychic burst of Dark energy that induces the Deluge. And when it's finished, if they survive, then the brain parasites infesting their head, the Benefactors, get strengthened by that Archedark magic and become more powerful—more capable of inducing perception changes in other people (called Auras, essentially multisensory illusions). It's literally an expansion of consciousness.

III - Metaphor

Barfield goes on to discuss how metaphor is one of the primary ways by which we understand the meaning inherent in poetry.

"Every modern language, with its thousands of abstract terms and its nuances of meaning and dissociation, is apparently nothing, from beginning to end, but an unconscionable tissue of dead, or petrified, metaphors."

This was a really interesting chapter in which he discussed several, I guess, going theories at the time concerning how language evolved. I won't go over all the competing theories that he shoots down, but his contention is that they essentially have it completely backwards. They talk about early language being simple, references to concrete things, and then accreting metaphorical meaning over time as we get more and more scientifically advanced.

"From being mere labels for material objects, words gradually turn into magical charms. Out of a catalogue of material facts is developed—thanks to the efforts of forgotten primitive geniuses—all that we know today as poetry."

Basically, the philologists of the time jumped to conclusions based on very little evidence and started making things up, like the "metaphorical period", in which the people in the "infancy of society" were an "exalted race of amateur poets." Philologist Max Muller gives an example of the process of metaphorical meaning being attached to words:

"Spiritus in Latin meant originally blowing, or wind. But when the principle of life within man or animal had to be named, its outward sign, namely the breath of the mouth, was naturally chosen to express it. Hence, in Sanskrit asu, breath and life; in Latin spiritus, breath and life. Again, when it was perceived that there was something else to be named, not the mere animal life, but that which was supported by this animal life, the same word was chosen, in the modern Latin dialects, to express the spiritual as opposed to the mere material or animal elements in man. All this is a metaphor."

Barfield convincingly dismantles this position ("It would be difficult to conceive anything more perverse than this paragraph.") and provides a more reasoned theory in the following chapter.

IV - Meaning and Myth

"'The evolution of language'—so Professor Jesperson sums it up—'shows a progressive tendency from inseparable irregular conglomerations to freely and regularly combinable short elements.'"

Rather than words slowly accumulating additional meanings, Barfield and Jesperson, who he references, say that it goes in the other direction. Words used to be richer and more full of meaning, and over time they lose aspects of it, as those aspects are specified and broken off into different words.

"We must, therefore, imagine a time when 'spiritus' or 'pneuma', or older words from which these had descended, meant neither breath, nor wind, nor spirit, nor yet all three of these things, but when they simply had their own peculiar meaning, which has since, in the course of the evolution of consciousness, crystallized into the three meanings specified."

This is a really cool idea. You can imagine this lost era when words had more richness and yet we do a decent job of capturing that richness in metaphor. Like, it's pretty easy to understand breath and wind and spirit as being related in some way. And while the way we understand those things as being in relation won't exactly match the mindset of pre-modern thinkers, we can approximate that lost-to-time state of consciousness in our own minds. I think at its best, fantasy is the ideal medium for doing this.

Barfield then talks about how these meanings are not invented by one person. It's more like they're discovered by great poets. This is a long passage, but it's one of my favorites in the book.

"Men do not invent those mysterious relations between separate external objects, and between objects and feelings or ideas, which it is the function of poetry to reveal. These relations exist independently, not indeed of Thought, but of any individual thinker. And according to whether the footsteps are echoed in primitive language, or, later on, in the made metaphors of poets, we hear them after a different fashion and for different reasons. The language of primitive man reports them as direct perceptual experience. The speaker has observed a unity, and is not therefore himself conscious of relation. But we, in the development of consciousness, have lost the power to see this one as one. Our sophistication, like Odin's, has cost us an eye; and now it is the language of poets, in so far as they create true metaphors, which must restore this unity conceptually after it has been lost from perception...

Chef's kiss. I love this. Meaning exists independently of any one of us; it's just waiting for us to reach out and grasp it. Like God extending his finger downward, and we have to reach up, as in Michaelangelo's The Creation of Adam. Creation, poetry, is neither top down nor bottom up. It occurs in the middle, the touching of our finger to God's.

What then of myths?

"These fables are like corpses which, fortunately for us, remain visible after their living content has departed out of them."

Myths, the combination of all the metaphors into old stories that survived the ages, are how we understand the meaning inherent in the language used by the ancients. For example,

"We find poet after poet expressing in metaphor and simile the analogy between death and sleep and winter, and again between birth and waking and summer, and these, once more, are constantly made the types of a spiritual experience, of the death in the individual soul of its accidental part, and the putting on of incorruption...

"Now, by our definition of a true metaphor, there should be some older, undivided meaning from which all these logically disconnected but poetically connected ideas have sprung. And in the beautiful myth of Demeter and Persephone, we find precisely such a meaning. In the myth of Demeter, the ideas of waking and sleeping, of summer and winter, of life and death, of mortality and immortality, are all lost in one pervasive meaning...

"Mythology is the ghost of concrete meaning. Connections between discrete phenomena, connections which are now apprehended as metaphor, were once perceived as immediate realities. As such, the poet strives by his own efforts to see them, and to make others see them again."

"Mythology is the ghost of concrete meaning." Sometimes this book is a little bit hard to parse, but then every once in a while Barfield will drop a banger like that out of nowhere. And it's a beautiful sentiment. None of these ancient people live, but their stories still do. The way of thinking that was then normal for them is now poetic to us. Their myths are full of meaning and can a shift us to a new state of consciousness, helping us see the world in a new (but very old) light.

I suppose in a way, if their stories are still with us, then so are they. Because, you know, even if only briefly, when we read these stories and get so immersed and absorbed in them, we inhabit the state of mind of the storyteller. We become identified with the protagonist and forget ourselves. It's like when you walk out of the movie theater after seeing The Matrix for the first time, and you feel like Neo, like you uploaded kung fu into your own brain.

That really is the goal of storytelling, isn't it? To share some process of interior change in the character with such high fidelity that the person experiencing the story feels like they themselves went through that change, thus expanding their consciousness and giving them a new way to see the world. Because stories, like I said, really are how we orient ourselves in the world, and how we decide what kind of person we want to be.

I won't go through the rest of the book because it gets a little bit disjointed and talks about a lot of interesting side tangents around poetry and metaphor and meaning. But I think the first couple chapters are really incredible. And the thrust of his argument, I totally buy it. It really helped me think about language in a way that I haven't been thinking for a long time.

But I'll leave you with one maybe saddening question.

"Is there some period in the development of a language at which all other factors being excluded? It is fittest to become the vehicle of great poetry, and is this followed by a kind of decline?"

If our language is fragmenting and becoming thinner in meaning, per se, then does that mean that the language is less capable of inducing changes in your state of mind? Is all of humanity's best poetry behind us? Are our own myths doomed to be forgotten because they don't have as much inherent meaning as the myths of ancient cultures? I'd love to hear your thoughts if you have any.

Thanks for sticking with me through this much-longer-than-I-expected post. I hope it wasn't too unfocused and conveyed some of my appreciation for the book. I'm planning to do this with all of the rest of the stack of books that I shared at the top, So if you want to keep up with that, subscribe to the Archefire Newsletter. I send one out every month, and I'll include links to any new essays of this sort that I write.