Photo by Nathan Dumlao / Unsplash

Keeping My Promises

It's been over two months since I published Two Different Classes of Story, and I still have an unfulfilled promise to keep. In that post, I laid out three big problems with translating a Dungeons and Dragons (D&D) campaign's story into a novel: inconsistent characters, pacing problems, and stakes-destroying magic. I delved into the first in Character Translation, and the second in Unwinding the Path. It's time to talk about the third problem.

For those unfamiliar, D&D has quite a complex magic system that has undergone many changes as new editions of the game are released. As of D&D Fifth Edition (5e) there are eight schools of magic, containing 520 spells. There are also several ongoing book series that occasionally introduce new aspects of magic that are accepted as canon, just to add to the chaos. And of course, since D&D's rules are really just a set of guidelines to help the players run a good game, they can always come up with homebrew spells if they want. It's a lot to keep track of.

But wait. If there are novels written within the D&D universe, doesn't that mean it is possible to adapt these magic systems into that medium? Yes.

Just not in the way I want to use magic in the Dance of the Sibling Suns series.

Magic Schools of Thought

The implementation of magic in fantasy stories is as varied as the stories themselves, but I've seen people broadly categorize magic systems and define the "purpose" of magic in several ways. Perhaps most famously, Brandon Sanderson coined his First Law of Magics:

"An author's ability to solve conflict with magic is directly proportional to how well the reader understands said magic."

Unstated in that definition is a key word: satisfactorily. If you want to solve conflict with magic satisfactorily, i.e. in a way that a reader will enjoy, then that reader needs to be able to understand the magic. Otherwise, they won't understand how the problem has been solved, and will feel as if the author inserted a deus ex machina because they couldn't think of a better way to progress the story. So that's one way to use magic in a story: to solve problems.

Steven Erikson returns to the roots of fantasy in mythology and what role magic served in those stories. He espouses a different school of thought: that magic is meant to evoke wonder, and should remain mysterious.

At the end of his post, Sanderson settles on a continuum between "hard" and "soft" magic systems, where hard magic systems are better suited to solving problems and soft magic systems are preserve the wonder in your story's world. And in the end, most magic systems are neither purely hard nor purely soft, but fall somewhere in the middle of the continuum. I think that's largely correct, but missing something.

Here, I can start to nitpick and say that it's not the magic system per se that is hard or soft; it's how much of the magic system the author reveals to the reader that determines where it lies on that continuum. In the video, Erikson even says:

We certainly follow specific rules. We have limits, but we certainly do not, at any time, feel obliged to explain them.

I ran into an interesting issue while writing An Ocean of Others that's related to this point, which I'll explain in next week's post.

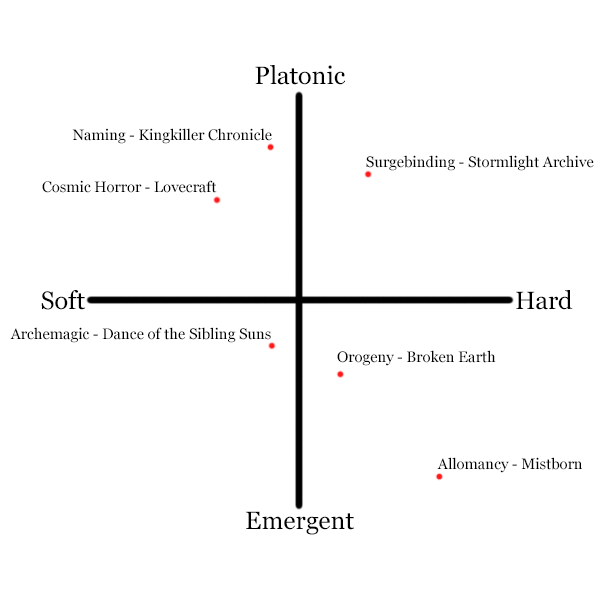

There's also this fascinating post on Platonic vs. emergent magic systems by author John Bierce, in which he explains why he presents an orthogonal scale of magic systems. Platonic magic is related to the ideal form of something. His example is fire magic, where a spell produces fire in reference to some pure, ideal form of fire. His example of emergent magic is also fire, but this time the spell just creates abrupt increases in temperature. The hard/soft continuum is about how much of the rules are presented to the reader; this new continuum more closely relates to the properties of the rules themselves.

Interestingly, his example shows that you can more or less achieve the same effect (fire magic) with both types of systems. While the hard/soft continuum alters what you can use your magic for in a story (i.e. solving problems vs. evoking wonder) the Platonic/emergent continuum alters the feel of a story, for lack of a better word.

Like Bierce says in his Reddit post, combining the two continuums allows one to create a sort of quadrant system for any given magic. So I did just that:

Bierce gives more examples in his post, but I tried to only include series I've actually read so I have some semblance of an idea of what I'm talking about. It's really hard to place the relative location of the data points on the Platonic-emergent axis, so I'm sure all of these could be refined with a deeper analysis.

In my opinion, Platonic systems blend quite well with soft systems. Something about ideal forms feels more... mystical to me, whereas emergent magic systems feel more like an extension of the laws of physics. However, that's just an opinion, not a rule. Any blend can work in the right story.

In sum, we've got two orthogonal continuums. Why do we use hard, rules-based magic? So we can resolve problems with it in a way that satisfies readers. Why do we use soft, mysterious magic? So we can make the world feel unpredictable and, at times, dangerous. Whether the system leans to the hard or soft end of the continuum, it can also lean either Platonic or emergent. And of course, there are probably countless other ways we could categorize magic systems, but let's move on for now.

So, how does any of this apply to D&D's magic?

The Economic Nightmare of D&D's Magic

If I were to use the D&D universe's magic in my book (setting aside copyright concerns), I think I'd be hard-pressed to turn it into a hard magic system. All of the spells are balanced from a game perspective, not from a story perspective. It seems easier to conceive of using this as a soft magic system in a book, but even then I'd have to be careful. Readers want internal consistency and logic in fantasy worlds, and the D&D spells break that in many ways. Sure, the internal logic of the magic itself might make sense, but let's look at two spells for example. First, Mending.

This spell repairs a single break or tear in an object you touch, such as a broken chain link, two halves of a broken key, a torn cloak, or a leaking wineskin. As long as the break or tear is no larger than 1 foot in any dimension, you mend it, leaving no trace of the former damage.

To cast this, the mage needs two lodestones, which are (as far as I can tell) just magnets. So with two magnets, they'd be able to repair any broken tool as long as it's a relatively minor break. Sounds like it would put a lot of blacksmiths out of work, or at least make them spend time doing other, more profitable things. You'd have to rethink your world's economy to accommodate the spell if you're including it in the story. Here's another: Plant Growth.

If you cast this spell over 8 hours, you enrich the land. All plants in a half-mile radius centered on a point within range become enriched for 1 year. The plants yield twice the normal amount of food when harvested.

Twice the normal amount of food! Almost all of human history is a story of privation and malnourishment. With this single spell, the entire way people live would change. Why wouldn't people just be doing this all the time? Well, maybe you have a good reason, but you'd have to spend precious worldbuilding time explaining that to the reader.

And that's just two spells. There are hundreds more in the spellbook! Who knows the untold ways these could be combined to break economies, worlds, reality itself? More importantly, it would be too easy to destroy the stakes of the story with magic like this.

As the tension builds up in a story, like a balloon filling with air, readers become more and more expectant that the tension will release in a satisfactory, climactic way. The balloon pops! It's what they've been waiting for, they want that release, and they want the characters to earn that release. If, instead, a magic-user whips out an as-yet-unseen spell that easily solves the problem... that's like the balloon deflating with a disappointing squeak as the air escapes the flappy opening. That magic hasn't evoked wonder, only sadness and regret.

Okay, so just don't write that spell into the story, right? Unfortunately, that's not a solution either. See, D&D fans are hardcore. They've meta-gamed the meta-game and know exactly how their characters' blend of skills can be used to bamboozle the Game Master. Many of them know their characters better than their own mothers. If we've established in a story that the D&D spell book is in play, and we don't use the perfect spell at the perfect time... well, expect some hate mail, angry Twitter replies, 1-star reviews, and worse. I'm not saying every D&D player is so rabid, and I wouldn't want to denigrate any community (especially one I'm a part of!) but I think we all know there are some, right? The internet brings out the worse in us.

I wasn't going to spend a ton of time reworking the story to avoids the hazards of 520 spells. I couldn't; the story was already largely in place, and I don't even want to get into the copyright issues. So what did I do with instead?

I changed the magic system nearly beyond recognition and created Archemagic. That's the topic of next week's post.